Jane Ord’s Cross-Stitch Sampler from 1832

I received a delightful belated Christmas gift today that only a historian, genealogist or cross-stitcher would get excited about. I don’t cross-stitch, but I am a genealogist and I have now immersed myself in learning the history of cross-stitching.

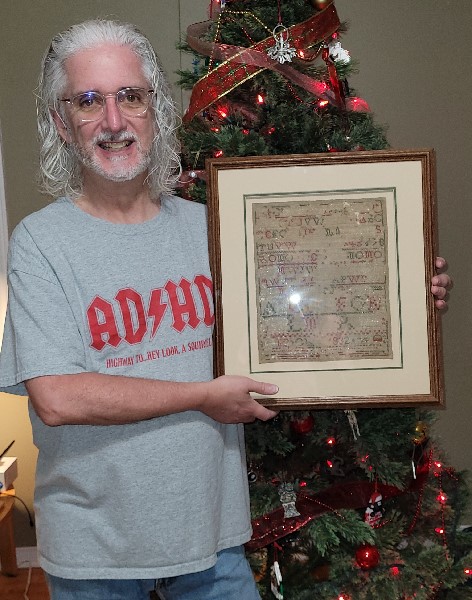

My newly acquainted cousin, Michael Dean, inherited the cross-stitch sampler from his mother many years ago, but the origin of the sampler remained a mystery until today.

Michael’s mother, Florence Jean Brown, was the younger sister of my grandfather, J. Stewart Brown. The two siblings had a falling out after the deaths of their parents, Tom Brown and Jane (Jean) Ord Stewart, and they never spoke to each other again. Jean’s family was living in Alberta and mine in Ontario. It’s likely that the physical distance contributed to the familial distance. But the distance was so real that my late father and Michael, who were first cousins, not only never met, but did not even know each other’s names.

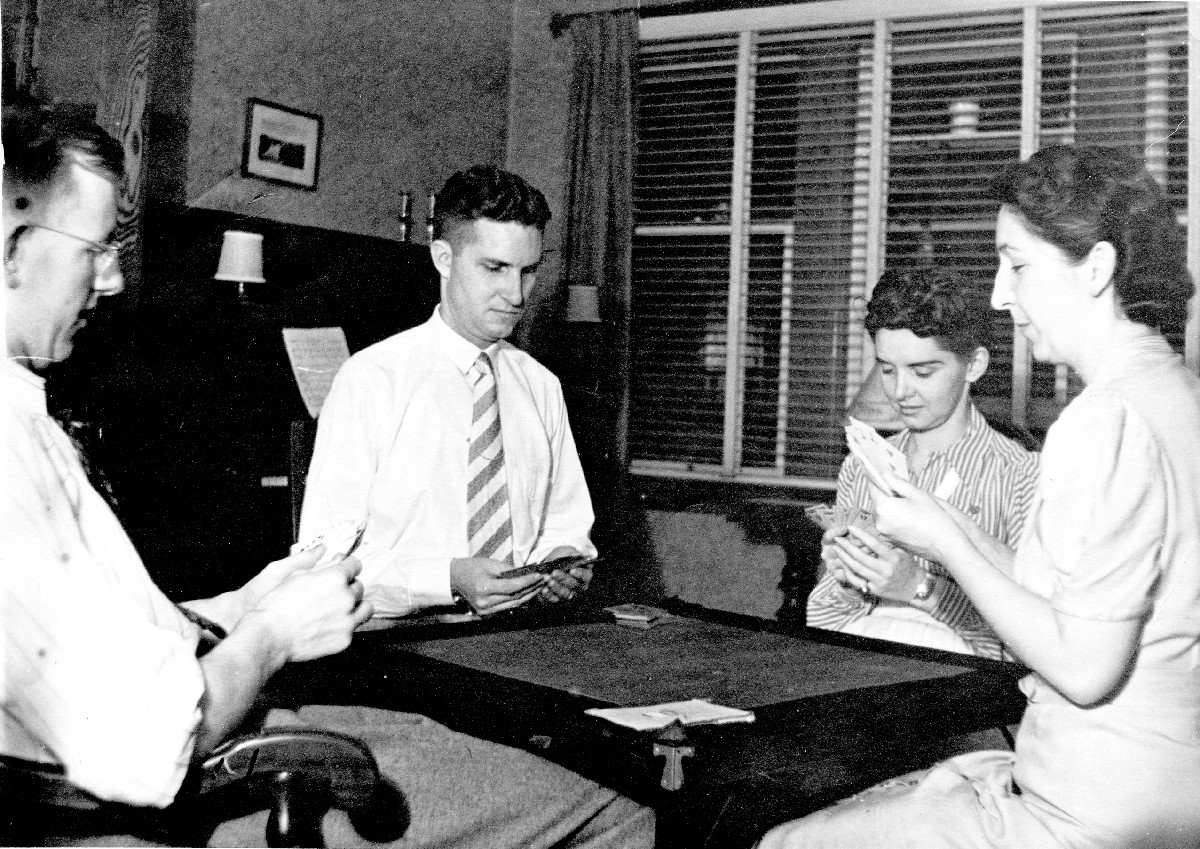

1938 or 39 – Basil Dean, Stewart Brown, Florence Brown, Harriett Brown (Jones)

In August 2021, Michael stumbled upon my family tree here on this website and contacted me regarding the entry about his parents. Since my database is privatized and Brown is an extremely common surname, Michael had no idea he was emailing the grandson of his mother’s brother. Upon realizing how closely related we are, we have had a most enjoyable time reconnecting our branches of the family over the ensuing months.

Determining the Provenance of the Sampler

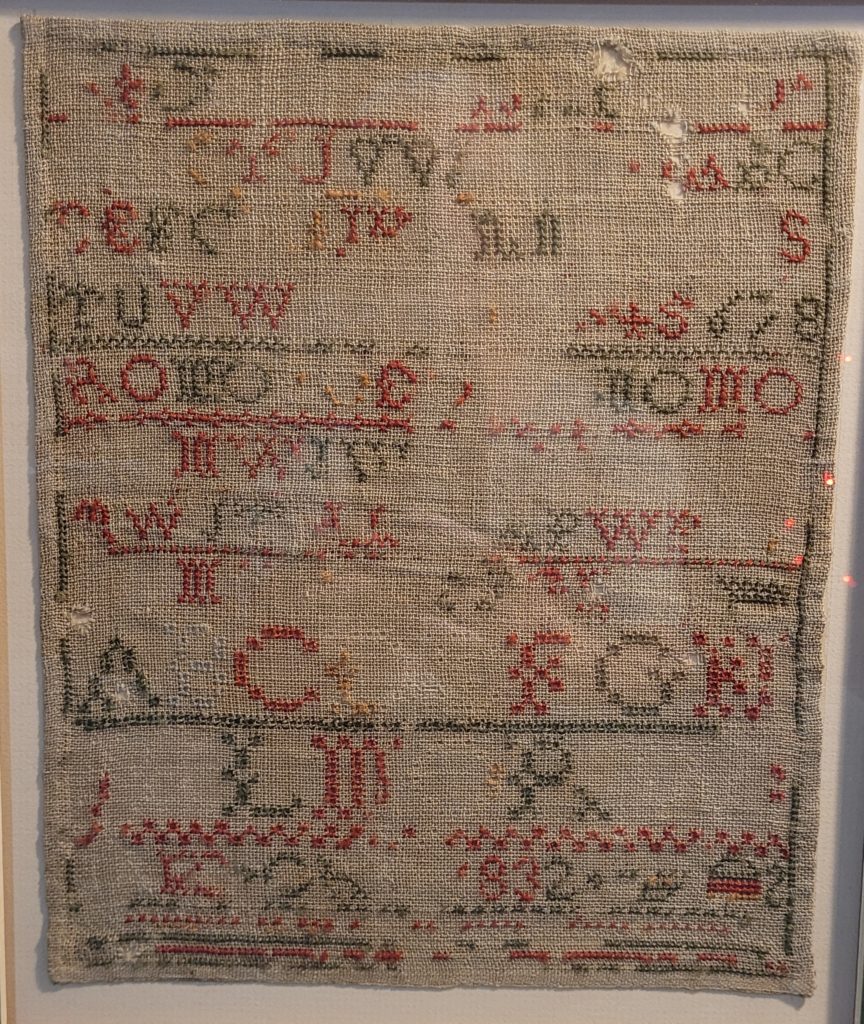

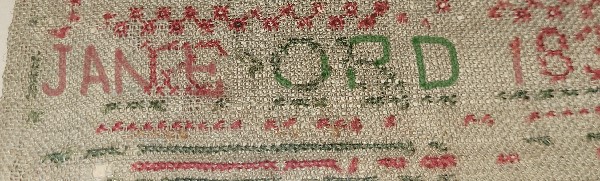

Michael sent me photos of the cross-stitch sampler seeking my assistance in identifying its provenance. All he know was that it allegedly came from his grandmother’s side of the family — the Stewarts and that it had the numbers “832” at the bottom, presumably a damaged “1832”, the likely date of its creation. This sent me on a quest to learn about the history of cross-stitch samplers, to see what this 190 year old piece of cloth might reveal for us.

Education for Girls in the 19th Century

In the early 19th century, even though boys and girls studied in the same one-room classrooms, their education was quite different under the British system. Education was somewhat of a luxury. Children were often put to work by age 8 and sometimes even as young as 4. Poor families depended on the additional income from their children, so there was little incentive to put children in school. The idea that children belonged in a classroom, rather than working in the local mill, was a new concept in the 1800s.

Girls were not deemed worthy of an academic education. If they were taught to be literate and numerate then they might seek social power, so education for girls emphasized domestic skills. While boys sat on one side of the classroom studying math, girls sat on the other side studying needlework.

Cross-stitching is a form of needlework where patterns are stitched into a piece of fabric with x-shaped stitches forming an image akin to early computer pixel art.

But how did one learn and pass on patterns for these works of fabric art?

What is a Sampler?

Photocopiers were non-existent. Paper was a rare luxury. The easiest way for a cross-stitcher to preserve a pattern idea was to stitch it into a piece of scrap fabric. Thus evolved the sampler.

I’d honestly never heard of a sampler before Michael contacted me. I had to Google the word to even know what he was talking about.

The sampler was a piece of fabric that the stitcher would use to practice their letter and number shapes. It also acted as a library to preserve copies of pattern ideas they had seen elsewhere and might want to use in the future.

As the craft became a formal subject in the emerging public school system in the early 19th century, cross-stitch samplers evolved into school exercises and examinations. A girl would quite literally work on her sampler for the term and submit it as her final exam project for grading in order to demonstrate, and be evaluated on, her skill level.

Typical school samplers contained alphabetical and numerical characters in different sizes and “fonts” as well as small pictures, various border patterns, and embellishments. They were often signed and dated by the creator. They became works of skill and pride and were often passed down from mother to daughter as heirlooms. Like this one…

Who Made this Sampler?

The title of this blog article is obviously a spoiler, but follow the discovery with me.

This item is clearly very old. It has holes in it. Many of the threads are worn and faded and some have come out over the years. Letters and numbers are missing. Needle holes in the fabric reveal partial outlines of missing characters. This has all the markings of a standard school sampler from the early 19th century.

Where one would expect to find the name and date of the girl who created it, we see damaged characters including what looks to be the letter ‘C’ and blank space where other characters are now missing. The ‘C’ initially threw me off, thinking it might be the initials of Catharine Stewart, the spinster aunt of Hugh Stewart (below) who raised him after he was orphaned.

The damaged signature is followed by the numbers ‘832.’ It’s an easy guess to suggest that the ‘1’ is missing and this should read ‘1832.’ But who was the stitcher? Which ancestor would have been a young teenage girl in 1832 on the Stewart side of the family?

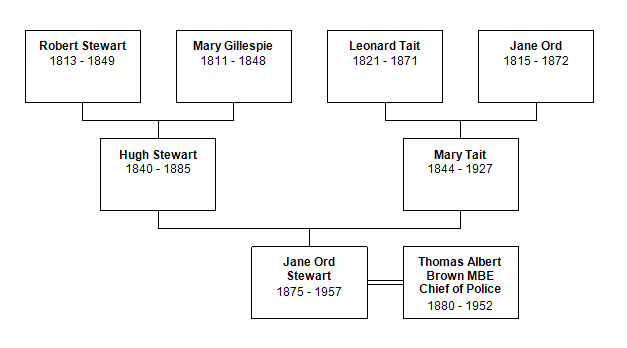

That really only leaves two women: Jane (Jean) Ord Stewart’s grandmothers (Michael’s great-great-grandmothers, and my 3x-great-grandmothers), Mary Gillespie (wife of Robert Stewart) and Jane Ord (wife of Leonard Tait.) Their children, Hugh Stewart and Mary Tait were the parents of Jean Ord Stewart.

It seems most likely that such an heirloom would be passed from mother to daughter, rather than through a son, so Jane Ord emerges as the preferred candidate. She would have been 16 turning 17 in 1832 — just the right age.

With me being the family historian, Michael asked me if I would become the caretaker of this heirloom into the next generation. I gratefully agreed.

It arrived in the mail this morning.

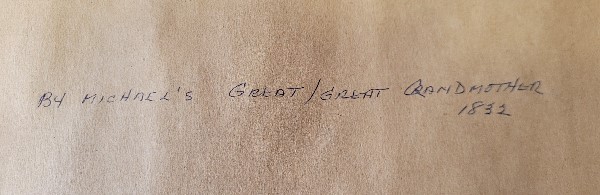

The inscription on the back of the frame confirmed the thoughts above:

Now that I was holding the actual object in my hands, upon closer examination, my naked eye could see what the camera could not reveal when viewing the photos that Michael had previously sent to me — the very faint shadow outline of the missing letters as well as the slightly enlarged holes where the needle and thread had previously pushed through. This revealed:

And now we can confirm, that this cross-stitch was made in 1832 at Whitecross Estate near Coldingham, Berwickshire, Scotland by 16-year-old Jane Ord.

Jane Ord, 1815-1872

Jane Ord was born at Eccles Lodge in the parish of Eccles, Berwickshire, Scotland near the border with England. The borderlands were a historically rough and troubled area. in the constant warring between England and Scotland over the centuries the troops of both countries regularly passed through these lands, burning, looting and killing. The area became notoriously lawless for centuries feeling little allegiance to either country, run by men known as Border Reivers. They were essentially pirates on land.

Jane Ord’s father, Robert, was initially an estate labourer, then moved up to be the steward of a farm called Annsfield on the Temple Hall estate near Coldingham, Berwickshire, Scotland, and finally as the estate manager (steward) for Whitecross estate near Coldingham.

In 1850, for reasons unknown, the Ord family immigrated to Canada and settled on a farm in rural Puslinch township, just south of the city of Guelph in Wellington County, Ontario, Canada. There Robert became a blacksmith working with his son-in-law, Jane Ord’s husband, Leonard Tait.

Jane Ord and Leonard Tait

Jane and Leonard had actually emigrated earlier about 1844 and settled initially in Beauharnois, Quebec, where their daughter Mary Tait was born in 1844. They then moved to Beverly township in West Flamborough, Wentworth County, Ontario before finally settling just north of there in Puslinch.

Mary Tait and Hugh Stewart

Jane Ord’s daughter, Mary Tait, would have been given the sampler by her mother. Mary Tait married Hugh Stewart, an orphan, who grew up on a farm in western Puslinch, southwest of Guelph, which is now a donkey sanctuary.

Hugh Stewart and Mary Tait moved to the nearby city of Hamilton where Hugh ran a small neighbourhood family grocery store, Tait and Stewart Grocers, with his brother-in-law, Robert Tait, at the corner of Hunter and Walnut streets and later at the corner of Fergusson and King William Streets.

Jean Ord Stewart and Tom Brown

Hugh Stewart and Mary Tait had a daughter Jane (Jean) Ord Stewart, named after her grandmother, Jane Ord, who made the cross-stitch sampler. Jean inherited the sampler from her mother, Mary Tait. Jean married Tom Brown, a police officer in Hamilton who went on to become Chief of the Hamilton Police where he was embroiled in the life of famous mobster Rocco Perri and personally oversaw the sweeping arrest of dozens of members of the Italian community, without due process, at the outbreak of World War II in what became known as The Italian Roundup. But that is a story for a future blog post.

Florence Jean Brown and Basil Dean

Jean Stewart inherited the sampler from her mother and passed it on to her namesake daughter, Florence Jean Brown, who married Basil Dean, a publisher for the Calgary Herald newspaper. She had no daughters so the cross-stitch was passed on to her son, Michael Dean, who has graciously gifted it to me.

Perhaps, someday, it may go to my daughter.

Sources

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sampler_(needlework)

https://www.historicalsociety.com/trends-thread-women-family-and-society-in-19th-century-samplers/

https://britishschoolsmuseum.org.uk/media/1678/first-threads-exhibition-booklet-lo-res.pdf

Ryk, this is wonderful. Our branch of the family is descended from Robert Ord and Mary Edgar’s son, Andrew. The story of the sampler is so interesting.