A Brown Family in Tandragee, Armagh, Ireland

Here I present my ancestral Brown family from Tandragee, Armagh, Ireland and all the known descendants. This Brown family were small-town merchants. Their ancestry can be traced back to Scottish Covenanters who likely emigrated from Lowland Scotland to Northern Ireland in the late 17th or early 18th century.

Origins

The Origin Of The Surname Brown

The name Brown is the third most common surname in the English language (behind Smith and Jones). The name Brown has three known origins:

-

- The first is a characteristic surname derived from the colour brown. It was likely used to describe an ancestor who had brown hair, brown eyes, a ruddy complexion, or possibly wore brown clothes. This etymology is the one most likely to apply to our family.

- In Northern Ireland it is also commonly an Anglicization of the Scots Gaelic Mac a’Bhrùithin, (pronounced “machk-a-broo-in” or “machk-a-vroo-in”, with the “ch” sound as in loch), which means “son of the judge”. Recent DNA evidence indicates that our Browns were of Lowland Scottish origin. Thus this etymology would not apply to our family. 1 2 3

- Dorward’s Dictionary of Scottish Surnames says (and other sources support) that Brown was one of the two surnames (the other being Smith) commonly chosen by Gaelic speaking Highlanders who were trying to integrate into English speaking areas but whose Gaelic patronymics were either too difficult to pronounce, or, among the anti-Gaelic racist attitudes of the day, considered to be unacceptable.

The Origin of Our Brown Family

Scottish Covenanters

Our Brown family originated in the Lowlands of Scotland. During the religious clashes of the 17th century our Browns are believed to have been Scottish Covenanters. As such they would have come under persecution from the Crown. Likely sometime in the late 17th century our Browns migrated (or possibly fled) from Scotland to Ulster, Ireland where they are believed to have settled in the area of Tandragee or Portadown, Armagh, Ireland.

Religious Tolerance in Pennsylvania, USA

Sometime in the early 18th century, likely around 1720, one branch of our family migrated from Ulster to Pennsylvania, USA. At the time, Pennsylvania was viewed as a place of great religious tolerance. It became a very attractive and popular destination for many persecuted Covenanters. Over the years this branch spread out across the United States.

Coming to Canada

Meanwhile another branch remained in Ulster. We know nothing for certain of their early years, but by 1840 they were residing in the village of Tandragee where they were bakers. In the late 19th century they migrated to Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, with one branch later migrating to Michigan, USA. By the mid-20th century we believe there were no more members of this family remaining in Tandragee.

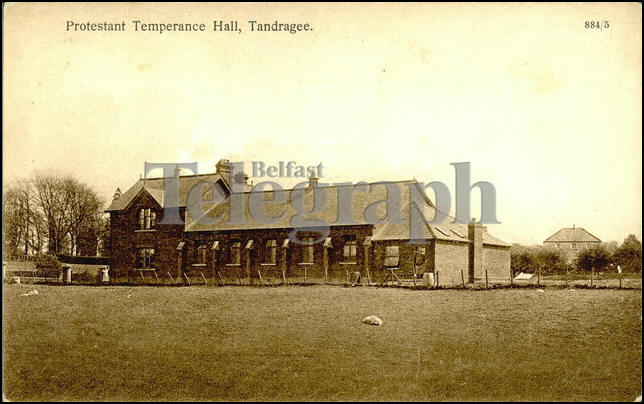

The Dark Side: The Orange Order

On the darker side: during the 18th and 19th centuries County Armagh was at the centre of the religious clashes between Catholics and Protestants. Tandragee saw its share of violence during this period (as described below). Out of these tensions came the birth of the Orange Order, a racist, anti-Catholic fraternal organization that modelled its organizational structure on Freemasonry, and which was founded in Loughgall, Armagh, a mere 10 km from Tandragee. Our Browns were staunch members of the Orange Order and its political cousin movement, the Irish Protestant Benevolent Society. Their shameful prejudices were taught in the family until the mid-twentieth century.

DNA Genealogy Research into the Origins of our Browns

FTDNA Group 39a

This family is listed at Family Tree DNA as Group #39a (formerly #64). The group contains two distinct sub-groupings:

-

- One branch which remained in Tandragee until the end of the 19th century and then immigrated to Canada;

- Another group who descend from an Alexander Brown who came from Ulster, Ireland to Reading, Pennsylvania in the early 18th century.

These two groups have a common ancestor likely born sometime in the 17th century. He most likely lived in Ulster prior to the Pennsylvania Browns coming to America, as it is unlikely that one of Alexander’s sons would have remained in Ireland and been the ancestor of the Tandragee Browns. It is far more likely that the Tandragee Browns descend from a brother or close cousin of Alexander. Thus we can establish the latest possible date for our common ancestor being approximately 1710 (the approximate birth age for Alexander Brown who came to Pennsylvania).

Covenanter Migrations from Scotland to Ireland

It is most likely that our ancestors came from Scotland to Armagh during one (or both) of the two major waves of Covenanter immigration: either during the 1640s as settler-soldiers from General Monroe’s Covenanter army, or, more likely, during the 1680s/1690s with the much larger migration fleeing the persecution of Covenanters during The Killing Time. A third possibility is a combination of the two: that one branch descends from an early settler-soldier from Monroe’s army and that the other branch were cousins who came over later fleeing persecution and settled in Armagh with their known relatives.

It’s unlikely that these branches would have kept in touch beyond second-cousins, thus the earliest our common ancestor was likely born would be ca. 1600. As such, historical and documentary evidence suggests that the most likely date range for our earliest common ancestor’s birth would be approximately 1600-1700.

DNA and Historical Evidence Agree

Whether we follow the DNA evidence or the historical evidence and deductive reasoning we arrive at the same time-frame for our earliest common ancestor being sometime in the 17th century.

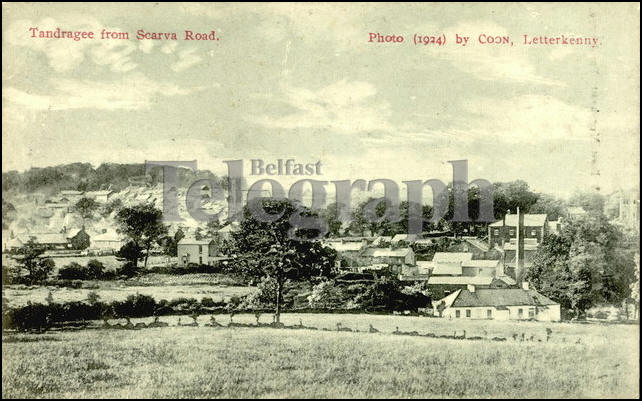

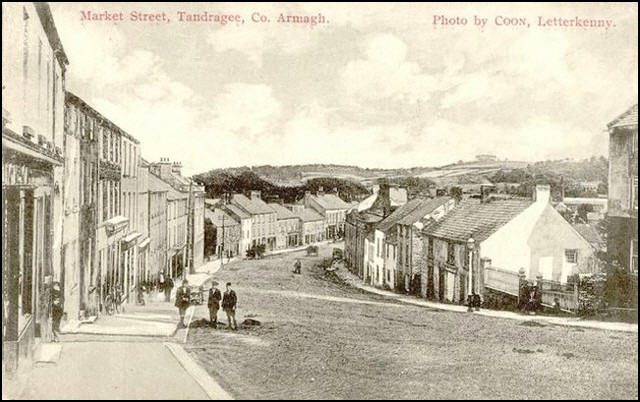

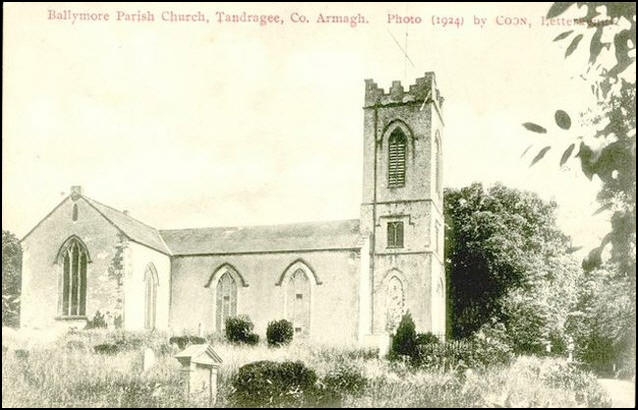

Tandragee, Ballymore Parish, County Armagh, Ulster, Ireland

Tandragee is a small town in Ballymore parish in County Armagh in the province of Ulster, Ireland, in what is today the United Kingdom state of Northern Ireland. The name ‘Tandragee’, in Irish, is Tóin re Gaoith. My best attempt at a translation is “back of the wind”.

Armagh, Ireland

The Bitter History of Tandragee

The history of Tandragee is, to a certain degree, a microcosm of the history of Ulster itself. To understand the history of Tandragee and the Scots-Irish culture from which our family came, one really needs to understand the history of the province of Ulster and the Plantations. Such a history is difficult to present as many sources are so politically charged and biased that it can sometimes be hard to distinguish history from political rhetoric.

This is a long history, but it is worth the read if you want to understand the culture of constant fighting and religious bigotry that our family came from. Tandragee and nearby Portadown were flashpoints for hostilities for 300 years. The issues in these villages were the same issues that we saw in Belfast and across Ulster that caught the world’s attention in the latter quarter of the 20th century . One of the most divisive organizations that fomented bigotry for over two centuries, The Orange Order (Orange Lodge), was birthed within walking distance of Portadown and Tandragee. The Battle of the Diamond took place withing walking distance of Tandragee and Portadown. We know our ancestors were heavily involved in the Orange Order; they could readily have been present at the Battle of the Diamond. We may never know for sure.

(The following history of Tandragee includes material excerpted from Tanderagee and the Presbyterian Meeting House 1829-2004, by Rev. Dr. Robin Greer, published by Tandragee Presbyterian Church.)

- 1. The Early Ulster Plantations - 17th Century

- 2. The Early Settlement of Tandragee - 17th Century

- 3. The Scottish Covenanters - 17th Century

- 4. The Irish Rebellion 1641-42

- 5. Resettling Ballymore and the Later Plantations - Late 17th Century

- 6. Tandragee in the 18th Century

- 7. The Troubles - Late 18th Century

- 8. Tandragee in the 19th Century

The Early Ulster Plantations in the 17th Century

A Common People With Common Origins

Ulster comprises the six counties of present-day Northern Ireland (Antrim, Armagh, Down, Fermanagh, Londonderry, and Tyrone) and the three bordering counties of Cavan, Donegal and Monaghan in the southern Republic of Ireland. From the earliest times there has always been a great deal of interactive traffic between northern Ireland and southwest Scotland as the two lands are separated by less than 20 miles of water. In fact the Gaelic-speaking Scots themselves were originally from Ulster, as the ancient Kingdom of Dalriada, which became the Kingdom of the Scots, was founded some 1600 years ago by Ulster Irish settlers. The language of Scots Gaelic evolved from the Irish Gaelic of these settlers. The people appear to have remained somewhat close to each other, as, through the early history of Scotland, whenever a royal or noble person was in trouble, it seems they frequently fled to Ulster.

The Earls’ Uprising

In the 16th century, while Protestantism swept through England and Scotland, Ireland remained largely untouched by the religious revolution and remained predominantly Roman Catholic. At the end of the 16th century Ireland was under the control of the English Crown. A failed uprising by many of the Ulster earls led to their replacement by English nobility.

Underpopulated Ireland Meets Overpopulated Scotland Under England’s Rule

By the early 17th century, the native Irish Catholic population of Ulster had been diminished by ongoing warring, while at the same time Lowland Scotland was over-populated.

The First Plantations

In an effort to deal with the overcrowding and consequent lawlessness on their lands, two Scots lairds, Hugh Montgomery and James Hamilton arranged with the Irish chieftain, Conn O’Neill, to settle large numbers of Lowland Scots on O’Neill’s lands, primarily in the counties of Antrim and Down.

The first large scale settlement of Scots began in 1605. These settlements were known as the “Ulster Plantations”. These new Scottish settlers were primarily Protestant (Presbyterian). In many cases the native Irish Roman Catholics were forcibly evicted from their lands in order to make room for the incoming Scottish Presbyterians. Understandably there was great resentment among the native inhabitants.

The Fears of King James VI & I

Meanwhile the new King James I of England (who was also King James VI of Scotland) was beginning to fear both uprisings in Ireland and political unrest in Scotland. He felt that the idea of forced plantations in Ireland might solve both his problems.

The Foundations of Religious Resentments

James began an intensive government program of settling Scots Presbyterians in Irish Roman Catholic Ulster. These settlers were settled into newly designed planned towns. These forced settlements and resettlements led to a volatile ethnic, religious and economic disparity with Scottish Presbyterian settlers living in the newly constructed town settlements, Irish Roman Catholic farmers in the surrounding lands, many of whom had been forcibly resettled, and English Anglican landlords and nobility trying to govern over these people. Ethnic and religious tensions ought to have been expected.

The Early Settlement of Tandragee – 17th Century

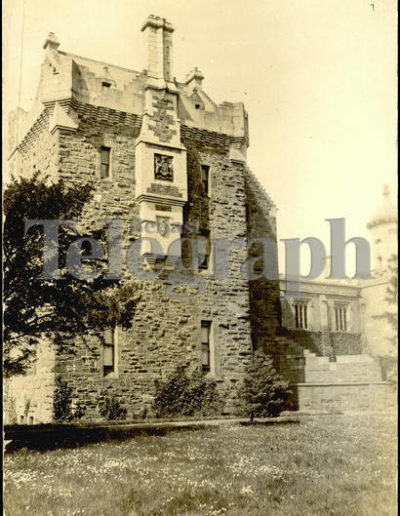

In the case of Tandragee, we see the religious tensions lived out. Tandragee was one of these “planned towns” described in the previous tab. The Project for the Plantation of Ulster of 1609 provided for four corporate towns in County Armagh. One of these was Tandragee, however Tandragee was never incorporated. It was planned on the lands of the former ancient kingdom of Oirthir (Orior) which had been ruled for centuries by the Uí Annluain (O’Hanlon) Clan. Sir Oghie O’Hanlon was the last of his long line to live in the ancient O’Hanlon Castle at Tandragee.

Following the 1598 Rising (during the Nine Years War), O’Hanlon and his family and followers were banished to Sweden. His estates were divided among various English Plantation grantees and in 1610, Sir Oliver St. John of Wiltshire was granted a substantial estate of 1000 acres of O’Hanlon land in Ballymore parish, including the former O’Hanlon Castle. English settlers began to build houses on the estate around it.

Sir Oliver St. John, Viscount Grandison of Limerick

Eventually Sir Oliver St. John was raised to Lord Deputy of Ireland and in 1617 he was created Viscount Grandison of Limerick. By 1619, he had 17 families planted in Tandragee. By 1621, he had rebuilt the castle, which became known as St. John’s Castle, and he oversaw the building of 20-30 English-style houses and a watermill. At this time, the settlers of Tandragee were entirely English.

Sir Oliver St. John, Lord Grandison, died in 1631 and his title passed through his niece to the present Earls of Jersey. His property in Ballymore passed to his great-nephew, Capt. John St. John, who resided in St. John’s Castle, Tandragee.

The Black Oath

In 1639, the ‘Black Oath‘ was introduced and required all Protestants living in Ulster to bind themselves to obey all Royal commands. The ‘Black Oath’ was designed to prevent the Presbyterian Scots in Ulster from aiding their fellow Scots in the Covenanter uprisings back in Scotland.

Our Browns were likely Scottish Covenanters and were most likely still back in Scotland at the time of the Black Oath.

The Scottish Covenanters – 17th Century

The Covenanter movement was a religious movement in Scotland throughout much of the 17th century that favoured the Presbyterian form of church government against the Episcopal form of church government favoured by the (now joint) English/Scottish Crown. The tensions ultimately let to civil war in Scotland and inspired revolutions in Ireland and England too.

Persecution & The Killing Times

The original Scottish National Covenant was proclaimed in 1638 and was supplemented by another document, The Solemn League and Covenant, in 1643. The Covenanters were zealous fundamentalist Presbyterians and were strong believers in religious freedom and non-interference from the state. Their movement was viciously put down by the Crown during the 1680s in a time that came to be known in Scotland as “The Killing Times”. Covenanters were hunted down and hundreds were summarily executed.

Escape to Freedom

In order to escape persecution many Covenanters fled to Ulster. When religious persecution followed them there, in the form of the Black Oath, and other oppressive measures, many of the Covenanters carried on to the American Colonies where they were attracted by the culture of religious freedom and frontier freedom from government interference.

In Scotland, the descendants of the Covenanters who remained behind eventually emerged as the Reformed Presbyterian Church, which, although small in Scotland, thrived in Ulster and in the United States. The influence of the Covenanters on the ultimate culture of zealous freedom that came to epitomize the formation of the United States of America is undeniable.

The Irish Rebellion 1641-42

At the same time as the Scottish Covenanters were beginning to stir in Scotland, trouble in Ireland was also brewing.

Irish Uprising 1641

In 1641, the Irish launched a rebellion under Sir Phelim O’Neill against the Protestant population of Ireland. Religious prejudices on both sides have led to two very different accounts of this rising. But it would seem that the Ulster-Scots were in a hopeless position, having been gradually disarmed by the English to prevent them from aiding their Covenanter kin in Scotland. The uprising claimed thousands of lives.

As part of this rebellion, in 1641 in Tandragee, Patrick Oge O’Hanlon captured the castle and town, presumably in the name of his displaced family.

The Invasion of Tandragee

In 1642, General Robert Monroe, Younger of Obsdale, was sent to Ulster to quell the rebellion. Monroe was commander of a Covenanter army from Scotland already seasoned from the Bishops Wars and the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. Sir Phelim O’Neill gave instructions for the assembling of Irish troops at Tandragee in an effort to oppose the approaching Scottish army. Monroe successfully occupied Tandragee for three days, burning the mills and several houses, in an event that came to be known as ‘The Invasion of Tandragee’. Patrick O’Hanlon fled and was eventually killed. However this did not extinguish the desire of the O’Hanlons to reclaim their ancestral lands and lesser skirmishes between the O’Hanlons and the St. Johns continued for at least another generation. General Munroe returned through Ballymore in 1646, but bypassed Tandragee, on his way to Benburb where he was later defeated by O’Neill. Many of Monroe’s soldiers remained and settled in Ulster following the rebellion.

Brutal Conflict

The conflict between the forces of Monroe and O’Neill was characterised as being extremely brutal even for its day with horrific stories of butchering of children. It probably did much to cement the foundations for later religious tensions in Ulster.

Civil War in England

Meanwhile, in England, civil war was breaking out at the same time as the Protestant English Parliament clashed with the Roman Catholic King Charles, thus distracting and weakening the British presence in Ireland.

Resettling Ballymore and the Later Plantations – Late 17th Century

Ballymore is Gaelic for “great town”. Ballymore parish was re-settled after the British Civil War of 1641-42 during the restoration of the British monarchy under Charles II. Prior to this time Armagh had been settled primarily by English. Thus, most Scots in the area came after 1642, however there was a Scottish settlment in the nearby village of Clare as early as 1619, prior to the Rebellion.

The Killing Times and John Brown of Priesthill

During the 1680s, after political shifts and a failed uprising, the Covenanters now found themselves on the wrong side of the law in Scotland. Covenanters were hunted down and killed on the spot. This brutal suppression became known as ‘The Killing Times’.

The most famous of the Covenanter martyrs was a man named John Brown who lived at Priesthill in Muirkirk parish, Ayrshire, Scotland, and who worked as a courier. John Brown was executed in 1685 by John Graham of Claverhouse, 1st Viscount Dundee, on his own doorstep in front of his pregnant wife and young children. John Brown’s family, like our Brown family, fled to Ulster.

Renewed Migrations

The 1680-90’s saw vigorous renewed migration of Scottish Covenanter Presbyterians to the north of Ireland to escape the brutal suppression of the failed Covenanter uprising. It is most likely during this time period when our Browns came from Scotland to Ulster.

The Battle of the Boyne

The Battle of the Boyne, in 1690, with William of Orange’s Protestants defeating King James II’s Catholic Jacobites, and the peace that followed it brought a new era of prosperity to Tandragee, at least for the Protestant victors. Local industries like milling and turning were revived and the weaving of linen became a staple industry. The smelting of iron appears to have died a natural death, but is still commemorated by a tract of woodland known in the locality as Forge Wood.

Marginalization of Catholics

The ongoing marginalization and oppression of Roman Catholics in nearby lands has been largely ingnored by British Protestant history writers until recent times. This ongoing oppression would eventually lead to the nearby village of Portadown becoming one of the founding flashpoints in the bloody hostilities between marginalized Catholics and colonizing Protestants.

Massive Scottish Immigration

The final large scale movement of Scots to Ulster happened in the 1690’s following the Battle of the Boyne when whole new towns and villages sprang up as Scots moved across the Irish sea to avoid famine in Scotland. There were no more wholesale plantations after this period as economic conditions in the north of Ireland were no better than Scotland, although there was still regular smaller scale movement between Ulster and Scotland.

Ulster-Scots

By the end of the plantation period an estimated 80%+ of the Protestant settlers in Ulster were Scots, the rest being English along with smaller numbers of French Huguenot, Welsh, Manx, German, Dutch and Danish. These other immigrants were eventually absorbed into the Ulster-Scots ethnic mix.

Ulster-Scots in a Lose-Lose Squeeze

The English administration transplanated Scottish Presbyterians onto Roman Catholic lands in Ulster, turning them into colonizing oppressors. Then the English administration persecuted those same Scottish Presbyterians whom at times they regarded as more troublesome than the Irish Catholics. Marriages carried out by Presbyterian clergy were not legally binding and Presbyterians could not hold public office. While a number of Scots converted to the Anglican Church of Ireland in order to find social acceptance and a number returned to Scotland, the vast majority remained in Ulster and maintained their Presbyterian faith. Over the next couple of generations many Covenanter families migrated to North America, most especially to Pennsylvania where they met with a culture of greater religious tolerance and acceptance.

Tandragee in the 18th Century

In the early years of the 18th century, the settlers in Tandragee decided to build a new church in Ballymore, near St. John’s Castle, whose mansion had previously been used as the place of Anglican worship.

It was likely around this time when the first branch of our family emigrated from Ulster to Pennsylvania.

The Presbyterian Church in Tandragee

It is not known exactly when the first Presbyterians began to worship in Tandragee. The earliest records date back only to 1825, however evidence suggests that some form of Presbyterian “meeting house” existed prior to 1825, but there are no records of any gatherings. There is a big gap between 1642 and 1825. Nearby Clare Presbyterian Church dates back to 1633 and it is likely that prior to 1825 any Presbyterians would have worshiped either at Clare or at the Church of Ireland parish church in Ballymore.

The School in Tandragee

In 1732 an English Protestant schoolmaster was installed to teach the English tongue in Ballymore parish. This implies that many of the parishioners were familiar with the Irish language (or possibly Scots Gaelic too, in the case of Highland soldiers who may have settled in the area).

Industry in Tandragee

In the early 18th century tanneries were common in the woodlands around Tandragee. By 1740, Tandragee was “a tolerably good village”.

In 1766, Ballymore parish was populated by 615 Protestant and 286 Roman Catholic families.

In 1789, a school was opened in Tandragee. And in 1796, soap making had become another local staple industry.

The Troubles – Late 18th Century

With the ethnic and religious situation described in the previous tabs it was inevitable that clashes between Catholics and Protestants would break out and that these clashes would take on a religious, not just political, character.

Fighting Erupts Locally

By the late 18th century there was great agitation in the country. In 1786, differences between the Protestant ‘Peep o’ Day Boys’ and the Roman Catholic ‘Defenders’ came to a head at Tandragee and a desperate fight took place. In 1787 another skirmish took place after which it is said that many well-to-do families “got up and left the country”. Further disturbances between Protestants and Catholics occurred in 1789, 1791, 1792, 1793.

In 1793, an Irish Militia Act required the listing, by parish, of all men between the ages of 18 and 45. These men were conscripted for service abroad for a term of three years. Exemption from service could be purchased.

Battle of the Diamond – Birth of the Orange Order (Locally)

In 1794 and 1823 Roman Catholic Defenders burned houses in the area. In 1795, troubles again arose, resulting in the Battle of the Diamond, which gave birth to the (Protestant) Orange Order. Tandragee became a stronghold for the Orange Order and still remains so to this day (2004).

This is Not Just History, It is Our History

For those of us who grew up half a world away from the locations of these events, it’s easy to miss the proximity. The distance from Tandragee to Portadown is 5 miles. Portadown to Loughall (the location of the Battle of the Diamond) is 5 miles. This is easy walking distance. Given the strong devotion of our ancestors to the Orange Order, it’s entirely possible that our ancestors were present at the Battle of the Diamond. No roll call was taken, so we’ll never know for sure.

Irish Civil War

Troubles throughout Ulster culminated in the Civil War of 1798. Tandragee escaped direct harm in this battle, although it is said that citizens of the town could be found on both sides of the fighting.

Tandragee in the 19th Century

In 1804, Tandragee, situated in rich countryside and within one mile of the Newry Canal, was inhabited by wealthy bleachers. Tandragee’s linen market was very successful. By 1814 there were 222 houses in Tandragee with a population of 1,081. By 1821 the population had increased to 1158 with 217 occupied houses.

In 1815, the Presbyterian minister of nearby Clare opened a private school in Tandragee. It seems reasonable to suggest that this may coincide with the earliest Presbyterian meetings in Tandragee. In 1819, the parish church was rebuilt and a public school was built, housing 60 pupils.

In 1823, there was a considerable disturbance in Tandragee and surrounding districts between Protestants and Catholics and a house and byres were burned.

Schools are well documented from 1824 onwards and in 1827 a Presbyterian congregation was established as an outgrowth of the nearby Clare congregation.

In 1831, a group of men from Tandragee deliberately disrupted celebrations of St. John’s Eve. During the disturbance on man was killed. Later that year there was an Orange Lodge demonstration in Tandragee in which 10,000 people attended. They are said to have “exhibited not less that 1000 guns openly and a great number of pistols.” In 1833 there was a procession after an Orange meeting at the castle gates which turned into a public riot. In 1834 there were more troubles again.

In 1836 the number of families worshipping in the Presbyterian congregation in Tandragee was 159, but only 53 actually resided in the town of Tandragee, the remainder were from adjacent lands.

By 1837 Tandragee was flourishing. The linen industry was extensive and there were several large flax mills which employed some 6000 people in the immediate area. There was also a meal mill on the nearby River Cusher. However, by 1846 the linen industry was in decline. There were also two hotels by this time.

During the years 1847-1855 there were no records kept for the Presbyterian congregation in Tandragee. Author Robin Greer suggests that this was due to great hardships suffered by the community from the Great Potato Famine of 1845-49 and the Crimean War of 1853-56. Later records imply that during this same period the minister of the congregation went without stipend for the equivalent of nearly six years. His stipend at the time was £40 annually. (In 2005 this would be equivalent to about £4000 or about $10,000 Canadian in modern currency.)

In 1861 the population of the town of Tandragee was about 2000 inhabitants. In 1863, Tandragee was first lit by gas. In 1888 there was also a successful spinning mill in town. In 1874 the Presbyterian congregation comprised about 65 households. In 1888 the census of the Presbyterian congregation was 248 adults and 206 children. In 2004 the membership was about 260 families.

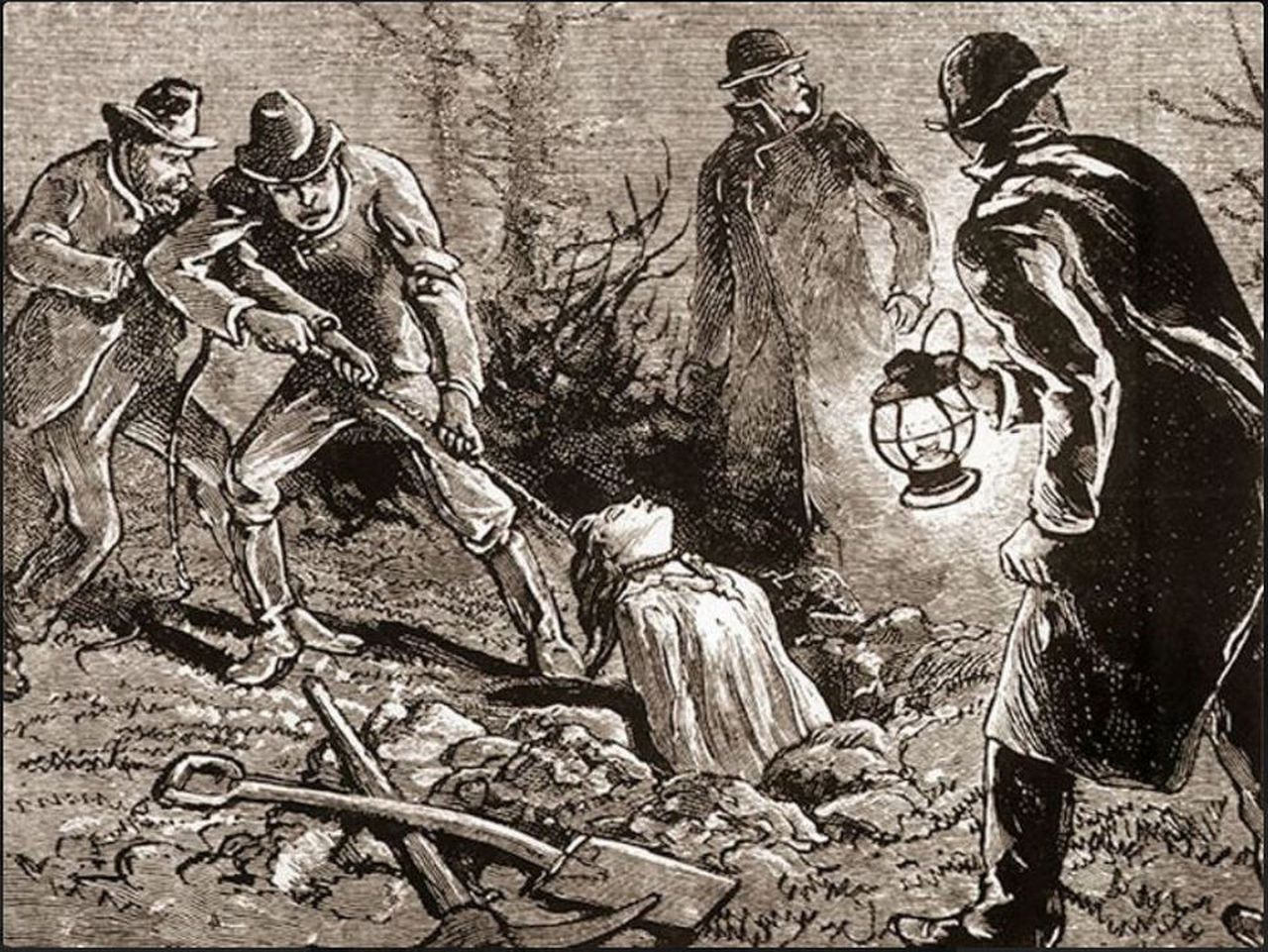

How the Dead Body Hung the Grave Robber

Jim Conway of The Lurgan Grapevine tells a story about how grave robbers developed a technique to allow them to work more quickly. Instead of digging up the entire grave, they would just dig up the area above the head and shoulders. Then they would tie a rope around the dead body under the arms and heave the body up through the hole, so they could rob it of any jewelry or other valuable possessions.

On one such occassion in a graveyard near Tandragee, the grave robbers threw the rope over a nearby tree branch for leverage, but the branch snapped back and the rope caught the robber around the neck and hung him. So the dead body hung the grave robber!

The Brown Family in Tandragee, Armagh, Ireland

The earliest records of settlers in Armagh are the 1630 Armagh Muster Rolls, which list several of the surname Brown. However, as we now know that our Browns were likely of Covenanter origins, they more likely arrived in Ulster either in 1642 among General Robert Monroe’s Covenanter soldiers or more likely among the refugees from the Killing Times after 1685. We know from DNA evidence that our ancestors were in Ulster before 1710.

Our Browns were staunch members of the Orange Order.

In 1928 on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the congregation a John George Brown of Maryland left a donation of £100 to the congregation. The congregational War Memorial for 1939-45 lists a W. Brown. The following persons are listed in the Armagh Muster Roll of 1630:

- George Brown, John Brown, Alexander Browne, George Browne, John Browne, Martin Browne, Nathaniel Browne, Richard Browne, Robert Browne.

However there is no indication where in Armagh any of these people lived.

Thomas Brown in Armagh, Ireland (possibly Derryaugh)

Thomas Brown, b. Abt 1780, Ulster, Ireland  , d. UNKNOWN, Ulster, Ireland. The unconfirmed but promising marriage registration for Robert Brown and Ruth Smith (shown below) indicates that Robert’s father’s name was Tom Brown. Nothing more is known about Tom.

, d. UNKNOWN, Ulster, Ireland. The unconfirmed but promising marriage registration for Robert Brown and Ruth Smith (shown below) indicates that Robert’s father’s name was Tom Brown. Nothing more is known about Tom.

As Thomas’ suggested son, Robert, was married in Tartaraghan and his children were born in Derryaugh (see below), it seems reasonable to suggest that Thomas may have come from nearby to Derryaugh, rather than from Tandragee.

Children

Tom’s marriage is unknown. He is suggested as the father of:

1. Robert Brown, b. 1812, Armagh, Northern Ireland, d. 18 Apr 1893, Tandragee, County Armagh, Northern Ireland

Robert Brown, b. 1812, Armagh, Northern Ireland  , d. 18 Apr 1893, Tandragee, County Armagh, Northern Ireland

, d. 18 Apr 1893, Tandragee, County Armagh, Northern Ireland  (Age 81 years). His information is presented below.

(Age 81 years). His information is presented below.

Derryaugh, Tartaraghan, and Tandragee, Armagh, Ireland

Robert Brown and Ruth Smith in Tandragee, Armagh, Ireland

Robert Brown, b. 1812, Armagh, Northern Ireland, d. 18 Apr 1893, Tandragee, County Armagh, Northern Ireland. He is suggested as the son of Thomas Brown, shown above. Robert married on 16 Oct 1839 in Tartaraghan, County Armagh, Ulster, Ireland to Ruth Smith, b. 1812, in or near Tandragee, County Armagh, Ulster, Ireland, d. 20 Jun 1902, Portadown, County Armagh, Northern Ireland (Age 90 years). Her parents are unknown, though onomastics would suggest their names were William and Prissella.

According to the family gravestone in Tandragee, Robert was born in 1812. He lived his life in Tandragee and he is buried in a very prominent location in the Tandragee Presbyterian Kirk yard along with his wife and several generations of descendants. Multiple records indicate that Robert was a baker.

Robert is listed in the 1881 Slater’s Royal National Commercial Directory for Tanderagee as a Baker on Church Street. He is the only commercial business owner surnamed Brown listed as residing in Tandragee in the directory.

A marriage record in the Ireland Diocesan and Prerogative Marriage License Bonds Indexes, 1623-1866, for Robert Brown and Ruth Smith married 1839 in Armagh, which appears to be correct for this couple. An unsourced entry at FamilySearch indicates this marriage was on 16 OCT 1839 in Tartaraghan, Armagh, Ireland, which is about 20 km northwest of Tandragee. Ruth Brown’s will indicates she had a cousin named Smith, supporting the likelihood that this is the correct marriage.

It appears that Robert and Ruth followed the traditional Scottish naming pattern.

Robert Brown and Ruth Smith’s grave stone, Tandragee Church yard.

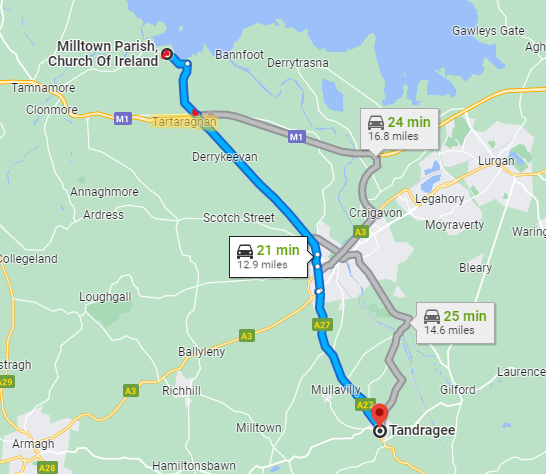

Derryaugh, Milltown, Armagh, Ireland

Family tradition tells us that our Brown family came from Tandragee. Robert and his family are buried in the Presbyterian cemetery in Tandragee. My grandfather named his bunkhouse “Tandragee” after his father’s birthplace. However, the birth records of three of Robert’s children have been located and they indicate that John, Robert, and Rachel were actually born at Derryaugh, Milltown Parish, some 13 miles (21 km) to the north of Tandragee. It would appear that they moved to Tandragee after their children were born.

The birth records for Prissella and Thomas have not been located, so they are recorded as being born in Tandragee, in keeping with family tradition. However, it seems more likely that they were born in Derryaugh, like their siblings.

Robert and Ruth were married in Tartaraghan which is located about 2 miles (3km) south of Derryaugh.

Robert Brown and Ruth Smith had the following children:

1. Prissella Brown, b. 1840, Tandragee, County Armagh, Ulster, Ireland, d. 11 Nov 1875, Tandragee, County Armagh, Ulster, Ireland

Priscilla Brown, b. 1840, Tandragee, County Armagh, Ireland  , d. 11 Nov 1875, Tandragee, County Armagh, Ireland

, d. 11 Nov 1875, Tandragee, County Armagh, Ireland  (Age 35 years). Shemarried on 16 Oct 1839 in Tartaraghan, County Armagh, Ulster, Ireland to John Johnson Mayes, b. 1841, probably County Armagh, Ulster, Ireland, d. 4 Aug 1889, Tandragee, County Armagh, Ulster, Ireland (Age 48 years).

(Age 35 years). Shemarried on 16 Oct 1839 in Tartaraghan, County Armagh, Ulster, Ireland to John Johnson Mayes, b. 1841, probably County Armagh, Ulster, Ireland, d. 4 Aug 1889, Tandragee, County Armagh, Ulster, Ireland (Age 48 years).

They had the following children:

-

- Samuel Johson Mayes, b. Between 1860 and 1889, Tandragee, County Armagh, Ulster, Ireland, d. 6 Jan 1937, Tandragee, County Armagh, Ulster, Ireland (Age ~ 77 years)

- He had descendants shown in my database.

- William James Mayes, b. 1863, Tandragee, County Armagh, Ulster, Ireland, d. 1 Feb 1881, Tandragee, County Armagh, Ulster, Ireland (Age 18 years)

- Samuel Johson Mayes, b. Between 1860 and 1889, Tandragee, County Armagh, Ulster, Ireland, d. 6 Jan 1937, Tandragee, County Armagh, Ulster, Ireland (Age ~ 77 years)

2. Thomas Brown, b. 1844, Tandragee, County Armagh, Ireland, d. 14 Feb 1881, Tandragee, County Armagh, Ireland (Age 37 years)

Thomas Brown, b. 1844, Tandragee, County Armagh, Ireland  , d. 14 Feb 1881, Tandragee, County Armagh, Ireland

, d. 14 Feb 1881, Tandragee, County Armagh, Ireland  (Age 37 years). Thomas married on 16 Oct 1839 in Tartaraghan, County Armagh, Ulster, Ireland to Margaret Steenson, b. 1856, Kilnaslee Townland, Donaghmore, County Tyrone, Ireland, d. UNKNOWN. Thomas died four years into the marriage. They had no known children.

(Age 37 years). Thomas married on 16 Oct 1839 in Tartaraghan, County Armagh, Ulster, Ireland to Margaret Steenson, b. 1856, Kilnaslee Townland, Donaghmore, County Tyrone, Ireland, d. UNKNOWN. Thomas died four years into the marriage. They had no known children.

Thomas’ birth and death dates are found on the family gravestone in Tandragee. His death registration in Banbridge is attached. His marriage was registered on 14 Sep 1877 in Dungannon parish, County Tyrone. Thomas is shown as a baker, age 22 (b 1855, which contradicts the gravetone and the death registration) as son of Robert Brown, from Tandragee. He married 19 year old Margaret Steenson, daughter of Andrew Steenson, from Kilnaslee Townland, County Tyrone. They were married in Carland Presbyterian Church, Donaghmore parish, County Tyrone. The marriage was witnessed by James Robinson, on the groom’s side, and George Gracey on the bride’s side.

Ruth Brown’s will indicates that she had a surviving daughter-in-law, Margaret Brown, in Portadown, Armagh, Northern Ireland. The 1901 census indicates that Margaret was born in County Tyrone in 1856, and that she was a widow in 1901.

3. John Brown, b. 19 Oct 1846, Derryagh, Milltown Cl, Armagh, Ireland, d. 1 Jul 1914, Hamilton, Wentworth, Ontario, Canada (Age 67 years)

John Brown, b. 19 Oct 1846, Derryagh, Milltown Cl, Armagh, Ireland  , d. 1 Jul 1914, Hamilton, Wentworth, Ontario, Canada

, d. 1 Jul 1914, Hamilton, Wentworth, Ontario, Canada  (Age 67 years). His information is presented below.

(Age 67 years). His information is presented below.

4. Robert Brown, b. 8 Dec 1849, Derryagh, Milltown Cl, Armagh, Ireland, d. 6 Aug 1873, Tandragee, County Armagh, Ireland (Age 23 years)rs)

Robert Brown, b. 8 Dec 1849, Derryagh, Milltown Cl, Armagh, Ireland  , d. 6 Aug 1873, Tandragee, County Armagh, Ireland

, d. 6 Aug 1873, Tandragee, County Armagh, Ireland  (Age 23 years). Robert died young with no known family. Robert’s information is found on the family gravestone in Tandragee.

(Age 23 years). Robert died young with no known family. Robert’s information is found on the family gravestone in Tandragee.

5. Rachel Brown, b. 15 May 1853, Derryagh, Milltown Cl, Armagh, Ireland, d. 10 Aug 1890, Wentworth, Ontario, Canada (Age 37 years)

Rachel Brown, b. 15 May 1853, Derryagh, Milltown Cl, Armagh, Ireland  , d. 10 Aug 1890, Wentworth, Ontario, Canada

, d. 10 Aug 1890, Wentworth, Ontario, Canada  (Age 37 years). She married on 7 NOv 1873 in Tandragee, Armagh, Northern Ireland to William James Brown, b. 22 Jul 1849 in Tandragee, Armagh, Northern Ireland, son of William or Robert Brown and Sarah. William was employed as an iron moulder in Ireland and in Hamilton. William married secondly on 13 Dec 1894 in Hamilton, Wentworth, Ontario, Canada to Elizabeth Leonard, b. 1854, Toronto, Ontario

(Age 37 years). She married on 7 NOv 1873 in Tandragee, Armagh, Northern Ireland to William James Brown, b. 22 Jul 1849 in Tandragee, Armagh, Northern Ireland, son of William or Robert Brown and Sarah. William was employed as an iron moulder in Ireland and in Hamilton. William married secondly on 13 Dec 1894 in Hamilton, Wentworth, Ontario, Canada to Elizabeth Leonard, b. 1854, Toronto, Ontario ![]() , d. UNKNOWN, Ontario, Canada.

, d. UNKNOWN, Ontario, Canada.

William is named in his mother-in-law’s will as residing “in America” at the time of her death. Her son John is also named as residing “in America” yet he resided in Canada. So she is using the term “America” to refer generally to North America, not just the USA.

Rachel is found in 1881 in Hamilton, Ward 6 with William and their first two children. Birth records confirm they were born in Ontario, thus William and Rachel were in Canada prior to 1878.

William is found without Rachel residing in Hamilton, Ward 7, where he was employed as a moulder. He was living earby to Rachel’s brother, John Brown, also in Ward 7, in 1891.

In 1901 William is found residing with his 2nd wife, Elizabeth, in Ward 6, Hamilton City as lodgers of Mary Garnet. It indicates that he immigrated in 1866, 22 years prior to his brother-in-law, John Brown.

A William J Brown died from chronic pneumonia at the Toronto General Hospital on 28 Sep 1907 and buried 16 Oct 1907, age 59, born 1848 in Ireland. He is buried in Necropolis Cemetery in a plot owned by Robert James Brown. He was a widower employed as a moulder. There is insufficient information to know if it is this William. His son Robert James Brown did move to Toronto.

Rachel and Willaim had the following children:

-

- Sarah Elizabeth Brown, b. 28 Sep 1878, Hamilton, Wentworth, Ontario, Canada, d. UNKNOWN. She married on 15 Jan 1896 in Wentworth, Ontario, Canada to William Henry Abby, b. 1877, Hamilton, Wentworth, Ontario, Canada, d. UNKNOWN. Sarah and William vanish from records after their marriage.

- Robert James Brown, b. 17 Aug 1880, Hamilton, Wentworth, Ontario, Canada, d. 17 Oct 1956, Toronto, York Co, Ontario, Canada (Age 76 years). Robert is found in 1901 in Hamilton, Ward 6, with his wife Grace and newborn daughter Mabel. He was employed as a roller. Robert married firstly on 19 Jan 1901 in Wentworth, Ontario, Canada to Grace Ellen Worthington, b. 13 May 1880, Burlington, Halton, Ontario, Canada, d. (To be updated). They had one daughter, Mabel (below). Grace and James split up shortly after the birth of their daughter and Grace become involved with another man and moved to Montana where they had a family. More information to be uploaded soon. Robert married secondly on 21 Nov 1904 in Wentworth, Ontario, Canada to Emma Arnold, b. 1883, Toronto, Ontario, d. 1974, Bancroft, Hastings Co, Ontario, Canada (Age 91 years). They had one daughter, Audrey (below).

- Mabel Brown, b. 21 Oct 1899, Hamilton, Wentworth, Ontario, Canada

, d. UNKNOWN. Updates pending.

, d. UNKNOWN. Updates pending. - Audrey Emma Brown, b. 1914, Cabbagetown, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, d. May 1977, Toronto, York Co, Ontario, Canada (Age 63 years) Updates pending.

- Mabel Brown, b. 21 Oct 1899, Hamilton, Wentworth, Ontario, Canada

- William Brown, b. 1883, Ireland, d. UNKNOWN. Possibly residing in 1901 in Middlesex North, lodging with the Clemens family, working as a farm labourer, immig 1888. Possibly the same William Brown: William Brown, 29, Irish, toolmaker ~~~ engineer, and wife Jean Brown 27, entered Detroit, Mich, USA, MAR 1909, from Hamilton, ON, brother of Charles Brown of 29 Stinton St, Hamilton ON, bound for ~~~ Michigan. (no marriage record found) (Note: This is almost the exact same time that his cousin, Robert Brown, moved to Detroit.)

John Brown and Sarah Cooke in Tandragee

John Brown, b. 19 Oct 1846, Derryagh, Milltown Cl, Armagh, Ireland  , d. 1 Jul 1914, Hamilton, Wentworth, Ontario, Canada

, d. 1 Jul 1914, Hamilton, Wentworth, Ontario, Canada  (Age 67 years). John was the eldest surviving son of Robert Brown in Tandragee, shown above. John married on 26 Sep 1867 in Milton, Lurgan, Armagh, Ireland to Sarah Cooke, b. 20 Apr 1854, Ireland

(Age 67 years). John was the eldest surviving son of Robert Brown in Tandragee, shown above. John married on 26 Sep 1867 in Milton, Lurgan, Armagh, Ireland to Sarah Cooke, b. 20 Apr 1854, Ireland  , d. 18 Mar 1919, Hamilton, Wentworth, Ontario, Canada

, d. 18 Mar 1919, Hamilton, Wentworth, Ontario, Canada  (Age 64 years). She was the daughter of William Lutton Cooke and Mary Fox from nearby Portadown, Armagh, Ireland.

(Age 64 years). She was the daughter of William Lutton Cooke and Mary Fox from nearby Portadown, Armagh, Ireland.

John and Sarah had seven children, of whom six survived to adulthood and immigrated in 1888 to Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, following John’s youngest sister, Rachel, who had immigrated in 1873 with her husband, William James Brown, also from Tandragee.

-

- Ruth Brown, b. 1869, Tandragee, County Armagh, Ireland

, d. 23 Sep 1875, Tandragee, County Armagh, Ireland

, d. 23 Sep 1875, Tandragee, County Armagh, Ireland  (Age 6 years)

(Age 6 years) - Mary Aileen Brown, b. 27 Feb 1870, Armagh, Northern Ireland

, d. 2 Nov 1941, Whitby, Ontario, Ontario, Canada

, d. 2 Nov 1941, Whitby, Ontario, Ontario, Canada  (Age 71 years)

(Age 71 years) - Robert Brown, b. 24 May 1875, Tandragee, County Armagh, Ireland

, d. 23 Oct 1944, Eloise, Wayne County, Michigan, USA

, d. 23 Oct 1944, Eloise, Wayne County, Michigan, USA  (Age 69 years)

(Age 69 years) - William John Brown, b. 15 Oct 1875, Tandragee, County Armagh, Ireland

, d. 15 May 1943, London, Middlesex County, Ontario, Canada

, d. 15 May 1943, London, Middlesex County, Ontario, Canada  (Age 67 years)

(Age 67 years) - Chief Const. Thomas Albert Brown, MBE Chief of Police, b. 12 Apr 1877, Tandragee, Armagh, Ireland

, d. 30 Mar 1952, Hamilton, Wentworth, Ontario, Canada

, d. 30 Mar 1952, Hamilton, Wentworth, Ontario, Canada  (Age 74 years)

(Age 74 years) - Anne Cardelia Brown, b. 4 May 1878, Tandragee, County Armagh, Ireland

, d. 1934, Niagara-on-the-lake, Welland County, Ontario, Canada

, d. 1934, Niagara-on-the-lake, Welland County, Ontario, Canada  (Age 55 years)

(Age 55 years) - James Cooke Brown, b. 16 May 1882, Tandragee, Armagh, Ireland

, d. 24 Mar 1950, Brantford, Brant County, Ontario, Canada

, d. 24 Mar 1950, Brantford, Brant County, Ontario, Canada  (Age 67 years)

(Age 67 years)

- Ruth Brown, b. 1869, Tandragee, County Armagh, Ireland

Further information on this family is presented on my Brown in Hamilton page.