The Chief and the King – 1. Introduction: Shadows

Part one of The Chief and the King: The story of the intersecting lives of Tom Brown, MBE, Chief of Police, and Rocco Perri, King of the Mob, in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, 1908-1944, by Ryk Brown.

Thank you to the invaluable original research conducted by

- James Dubro, author of King of the Mob: Rocco Perri and the Women Who Ran His Rackets.

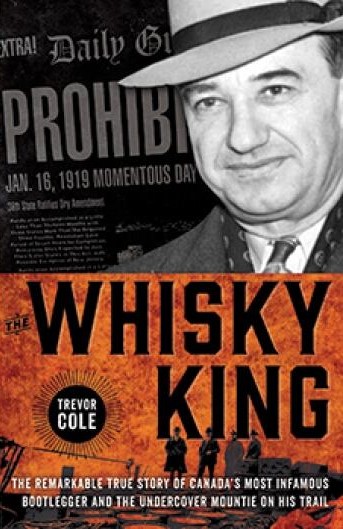

- Trevor Cole, author of The Whisky King: The remarkable true story of Canada’s most infamous bootlegger and the undercover Mountie on his trail.

- Antonio Nicaso, author of Rocco Perri: The Story of Canada’s Most Notorious Bootlegger

My research into this story is ongoing and not yet complete. Subsequent chapters will be released as research continues and time permits.

Shadows

Criminal corruption rarely takes place in full view and is rarely written down. Written documents can too easily become evidence which can lead to convictions. So, criminals, and the corrupt public figures they work with, have an incentive to not keep a written record of their activities.

When a police officer took a bribe in the 1920s, no receipt was issued. It wasn’t recorded in a ledger. It was just a wad of cash stuffed in a plain envelope, discretely delivered, and slipped into a coat pocket. In a pre-digital era, it was relatively easy for the recipient to hide that cash and spend it without leaving a trail of evidence. And, when everyone else was taking bribes, it was hard to say no.

Where records do exist, they’re often encoded. For example, in the case against Al Capone, FBI Agent Elliot Ness needed the cooperation of Capone’s bookkeeper in order to translate the secret language of Capone’s ledgers in order to convict him.

It is often the case that, during the course of an investigation, written documents have a mysterious habit of disappearing. That leaves both detectives and later historians with a dearth of documented evidence. Sometimes, we are left with only inferences, innuendos, and implications of what might be true. The actual truth remains in the shadows.

Two Immigrants, One Foreigner

This is the story of two men whose lives intersected before, during, and after the Prohibition era in a way previously overlooked by history. While they were both immigrants to Canada, only one was considered a foreigner. The other was considered a native citizen. One was an outsider; the other was an insider.

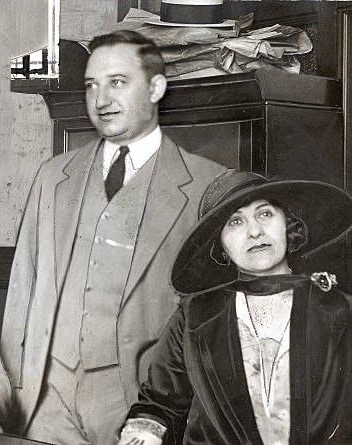

This is the story of Rocco Perri, who immigrated as a boy from Calabria, Italy, eventually settling in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, where he embarked on a life of organized crime and rose through the ranks to become “King of the Mob.”

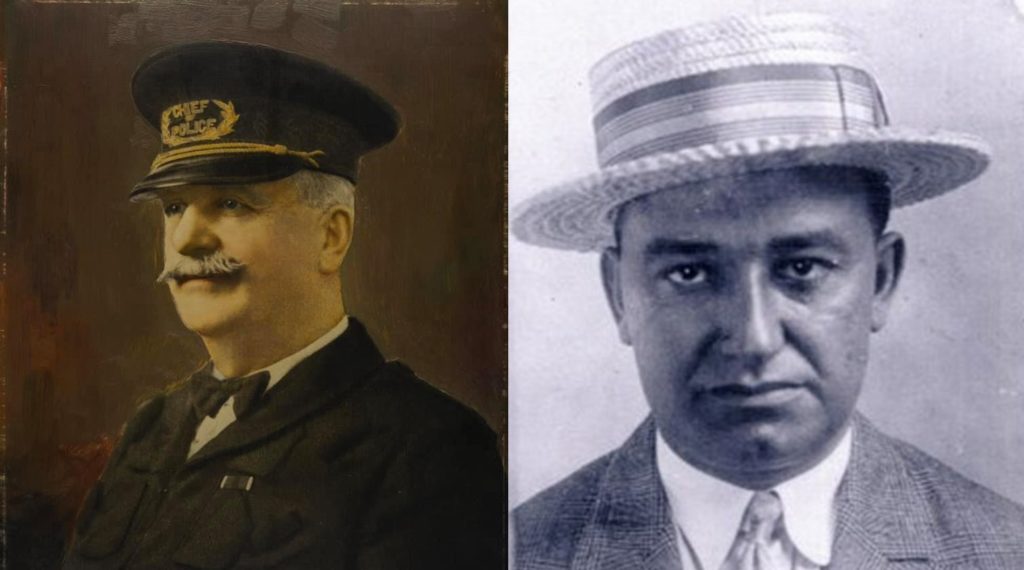

This is the story of Tom Brown, MBE, who immigrated as a boy from Armagh, Northern Ireland, to Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, where he became a police officer and rose through the ranks to become Chief of Police.

This is the story of their parallel and intersecting lives in the city of Hamilton through the first half of the twentieth century until Tom Brown eventually put the untouchable Rocco Perri behind bars. Well…sort of.

Tom Brown, MBE, the Esteemed Chief of Police

It was always a story told with pride in my family that my laudable great-grandfather, Tom Brown, had been Chief of Police in Hamilton, Ontario, during World War II. He guarded King George VI and Queen Elizabeth on their Royal visit to Hamilton. He was awarded a Member of the Order of the British Empire (MBE) – equivalent to the modern Order of Canada. He served in the Boer War. He conducted himself heroically during the violent 1906 Hamilton Street Railway strike. He was technologically progressive and introduced two-way radios into police cars. He was beloved by the officers who served under him. The Hamilton Spectator described him as “always kindly and sympathetic and at all times had a fatherly understanding towards junior officers.” All of these great things are true about him, but they don’t tell the whole story.

Tom Brown was “always kindly and sympathetic and at all times had a fatherly understanding towards junior officers.”

Hamilton Spectator, 1944

Tom Brown died more than a decade before I was born, so I never met him. As a child, I knew only the stories of his glorious achievements. As an adult and family historian, I learned there was more to his story. He was a very human and very flawed person, just like most of us. He achieved great things, and he also participated and perpetuated horrible things. He was neither sinner nor saint. He was both.

In addition to the great things Tom Brown accomplished, he also perpetuated a multi-generational legacy of family violence. He led the Hamilton Police Force through a shameful moment in Canadian history, which was the unjust internment of innocent Italians at the outbreak of World War II. And he almost certainly participated in an “accommodating” relationship with Rocco Perri and the Hamilton-based Canadian mafia.

The Italian Internment

With the outbreak of World War II, long-held anti-Italian racist views gained license although the federal government’s invoking of The War Measures Act. It allowed the government to apprehend without cause and imprison without trial any Italian who was alleged to have fascist sympathies. Thousands of Italians were branded as “enemy aliens” and viewed as potential terrorists, spies, and saboteurs simply because of their nationality. By 1943, over 600 Italian-Canadian men had been arrested and sent to internment camps. Seventy-four of them came from Hamilton. None were ever charged with any crime.

While the population of Hamilton comprised only 1.5% of the total population of Canada in 1940, 12% of the detainees came from Hamilton. Put another way, the number of Italians apprehended in Hamilton was ten times higher than in the rest of Canada.

These Italian men were not arrested individually, separately, and gradually over the six-year course of the war. One of the startling truths was that, in Hamilton, nearly all of them were arrested in one single day….

…in just two hours….

…over the dinner hour.

Nearly all of them were arrested in one single day

in just two hours

over the dinner hour.

On June 10, 1940, a mere ten minutes after Benito Mussolini, Prime Minister of Italy, announced the entry of Italy into WWII in support of Hitler, a coordinated and nearly simultaneous series of raids commenced across the country, overseen by the RCMP but conducted by local police forces. Nearly 600 Italian-Canadians were arrested in a single day. 30,000 more were designated “enemy aliens” and were required to register weekly at their local post office for the duration of the war.

The RCMP lacked the human resources to administer all these raids and registrations across the country at the same time. They had to rely on local police forces to do much of that work. These things could not have happened in cities across Canada without the full involvement of the local chiefs of police. In Hamilton, that meant that my great-grandfather must have been involved.

It was a difficult truth for me to discover and come to terms with, that not only was my great-grandfather involved in the wrongful arrest and detainment of seventy-four Italian men in Hamilton, but he was actually in charge of it; a fact that he proudly bragged about:

“Within an hour or two, practically all the supposedly dangerous members of Hamilton’s considerable Italian population were safely under lock and key, and were thus deprived of any chance of endangering our industrial population.”

– Police Chief Tom Brown, Report to City Council, Hamilton, Ontario, Dec. 1940.

wikipedia

Racism, Xenophobia, and the Orange Order

The Orange Order is a Northern Irish Protestant fraternal organization, founded in 1795 just outside of Portadown, Armagh, Ireland. It was founded on anti-Roman Catholic, British nationalist, racist, xenophobic, and supremacist ideals. Through the 19th century, it spread throughout the British Empire and colonies and remained firm in the later Commonwealth. It remains present and active in Canada and around the world to this day. Much of present-day extremist, alt-right culture in North America, including the Ku Klux Klan, can trace its historic ideological roots to the precepts and principles of the Orange Order.

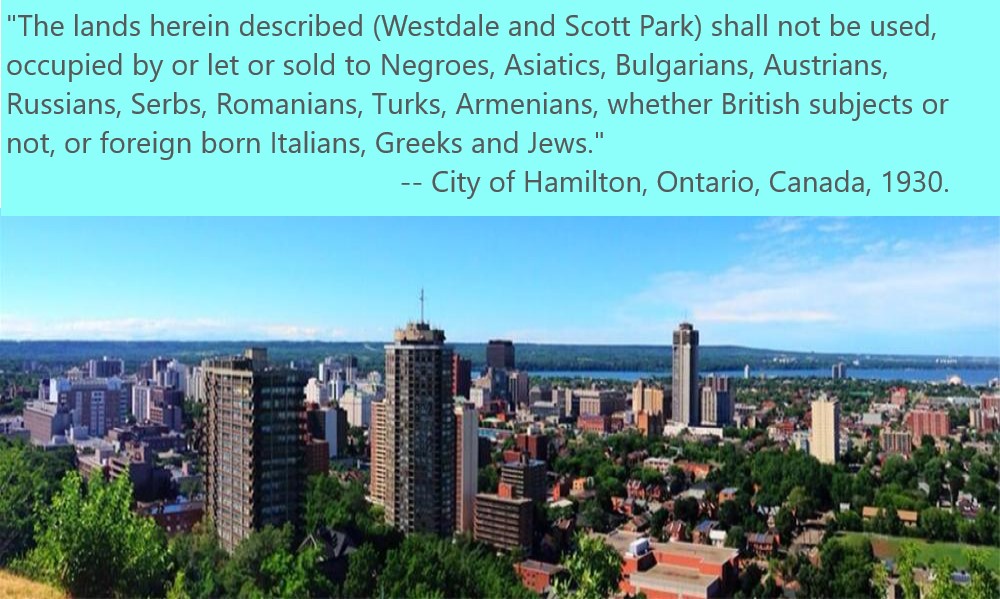

William Smyth, in his book, Toronto, the Belfast of Canada: The Orange Order and the Shaping of Municipal Culture, shows how, in the formative decades of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, in the nearby city of Toronto, Ontario, Canada, most major municipal government positions, including nearly every mayor, were filled by members of the Orange Order. The same was true in Hamilton. John Weaver, in his book, Crimes, Constables and Courts: Order and Transgression in a Canadian City, 1816-1970, a comprehensive study of police culture in the city of Hamilton, shows that, prior to World War II, 85-95% of Hamilton police officers were of Northern Irish, Scottish or English (i.e. British Protestant) origins. The first Italian was not admitted to the police force until after World War II. In 1930, Hamilton City Council passed legislation restricting where non-British citizens could live in Hamilton.

Tom Brown was born just outside of Portadown, Armagh, Ireland, where the Orange Order was founded. He grew up immersed in a multi-generational history of racism and was surrounded by sectarian violence between Irish Protestants and Catholics. He was a member of the Orange Order and had the “honour” of riding the White Horse in the annual local Hamilton Orange parade. His wife’s cousin, William Stewart, Mayor of Toronto (1931-1934), was likewise a member of the Orange Order and also rode the White Horse in the Toronto Orange parade.

Racism and xenophobia were widespread and socially acceptable in pre-World War II Canada. We have yet to eradicate that legacy.

The wrongful internment of Italians was not simply motivated by exaggerated fears of fascism. It was not simply racism and xenophobia. It was certainly all of these things, but there was another motive as well. There was something else hidden in the shadows.

Dethroning the “King of the Mob”

Through the 1920s and 1930s, Rocco Perri had become the undisputed founding godfather of the mafia in Canada. He was dubbed “Canada’s Al Capone”, “King of the Mob”, “The Whisky King”, and “Canada’s Most Notorious Bootlegger.” He was a crime figure every bit as large as Al Capone and deserving of similar infamy. His wife, Bessie Starkman, was known as “The First Female Crime Boss.” His senior lieutenant and successor, Antonio Papalia, founded Canada’s first mafia dynasty that reigned for half a century.

Rocco and Bessie Perri were made of Teflon. Criminal charges just didn’t stick to them. The FBI had had similar challenges with Al Capone. It’s easy for us today to forget that anti-racketeering laws hadn’t been written then, and conspiracy is one of the most difficult crimes to prove, so it was extremely difficult to convict mob bosses of any serious crimes as they always remained at arm’s length from the crimes they directed.

During the Prohibition years of the 1920s, mobsters were treated like folk heroes because they supplied the much beloved beer and whisky that thirsty Canadians genuinely wanted. Prohibition was deeply unpopular so there was little support among the public for prosecuting mobsters at the time. Even so, getting away with such brazen criminal acts without being prosecuted required corrupt support from police, judges, and politicians.

While there is no surviving evidence to show that my great-grandfather, a sergeant at the time, ever personally received a bribe from Rocco Perri, the same is true for most of his colleagues. Rocco and Bessie were reputed to have had every important cop, magistrate, and politician on their payroll. In the early 1920s, Police Chief William Whatley (a mentor to Tom Brown) was believed to have been so “in bed” with Rocco and Bessie that he was accused of being literally in Bessie’s bed having an affair with her, seemingly with Rocco’s blessing. If that’s what it took to have the police chief on his side, Rocco appears to have turned a blind eye.

After Prohibition was abolished in 1927, the public no longer needed mobsters to supply them with alcohol. So, the Perris turned to selling drugs, which was far less glamourous and began to turn public sentiment against mobsters.

In 1930, Bessie was gruesomely murdered, allegedly at the hands of a rival mob family from Buffalo. With her murder, any residual illusion of the folk hero mystique was gone, and public sentiment turned into fear and resentment towards mobsters. But the government still lacked the legislative tools to convict mob bosses like Rocco Perri. That is, until World War II handed them the opportunity they needed.

On September 3, 1939, Prime Minister Mackenzie King’s government invoked the War Measures Act which gave “tough on crime” politicians and police the tool they needed to finally put Rocco Perri and his fellow mobsters behind bars. While it was ostensibly invoked to pursue fascists, and while it was certainly motivated by cultural xenophobia and racism, it also enabled the RCMP and local police forces to apprehend every major mafia figure in the country simply by labelling them as fascists.

However, it turns out that shutting down the mob is not as simple as arresting all the leaders, as their connections are deep and broad. Sometimes you have to play one side against the other.

The New York vs. Chicago Rivalry

The mafia transcended international borders. The two major rival powers centres in North America were New York City and Chicago. The Genovese family, under Charles “Lucky” Luciano, ruled New York and Al Capone ruled Chicago. Rocco Perri in Hamilton was allied with Al Capone in Chicago, whereas the Magaddino family in Buffalo, New York, were allied with Luciano in New York City. Hamilton and Buffalo are only an hour’s drive from each other, and Hamilton became a battleground for the power struggle between the two rival syndicates.

The Uniform vs. Detective Rivalry: Appeasement vs. Confrontation

There was another rivalry emerging during the 1930s. Even though public sentiment had swung away from admiration to disdain towards the mafia, how to deal with the problem of the mafia was not so clear cut. Two rival approaches appear to have emerged within the Hamilton Police Force as to how to deal with organized crime: appeasement versus confrontation.

Appeasement involves working with the mob to reduce violent crimes that put the public at risk while turning a blind-eye to less-violent crimes. In other words, as long as the mob doesn’t “soil their nest” then they can keep earning money through illegal means. The downside of this strategy is that it entails police corruption to work. The police have to willingly ignore crimes.

Confrontation involves “zero tolerance” for the mob’s criminal activity. It involves increased raids on criminal businesses and lots of very public arrests. While it’s a more honest and ethical strategy, if it doesn’t work then it risks making things worse. It could enflame the situation and could lead to increased violence in the streets.

If you’ve seen the TV show, Sons of Anarchy, these two approaches to dealing with organized crime were embodied by Police Chief Unser (appeasement) and Deputy-Chief Hale (confrontation).

These differences in preferred strategy became so divisive that they threatened to rip the police force in two. It got so bad that there were discussions about having two separate police forces in Hamilton, one for detectives and another for uniformed officers, each with its own separate police chief. Evidence hints that the Detective Division, under the leadership of Inspector Joseph Crocker, favoured a strategy of confrontation, whereas the Uniformed Division, under the leadership of Inspector Tom Brown, appears to have favoured a strategy of appeasement.

Tom Brown was an old-school street cop. He knew how things really worked on the streets. Rather than try to take down the mob, he appears to have preferred to try to work with them. One can almost picture Tom Brown pounding his fist on his desk exclaiming, “Look, I’ve spent my entire career on the streets dealing with Perri’s gang. Confronting them head-on isn’t going to work. It’s just going to blow up in our faces.” And he was right. That’s exactly what did happen, as we’ll see momentarily.

Police Chief Ernest Goodman, himself a former Inspector of Detectives, appears to have supported his detectives in favouring a strategy of confrontation. Evidence shows that the Hamilton Police pursued a confrontational strategy and began cracking down on Rocco Perri’s gang through the 1930s, and the consequences were violent.

The Chief is Dead, Long Live the Chief

The mob rivalry between Buffalo and Hamilton may have had an impact on two key moments in the career of Tom Brown, namely his appointment as Chief in 1938 and his later retirement in 1944. The sequence of events surrounding these two moments is striking to the point of being suspicious. As is so often the case in this story, written records are lacking, so we don’t know what actually went on behind the scenes. More shadows.

In March 1938, an attempt was made on Rocco Perri’s life utilizing a car bomb. It was attributed to the rivalry between the Magaddino family and Rocco Perri. Police Chief Ernest Goodman attempted to mediate a face-to-face meeting between the two parties. The meeting failed to bring peace.

A few months later, on Sunday, November 27, 1938, Chief Goodman died “suddenly” after an unspecified “short illness.” What was the sudden fatal illness? Was it suspicious? We don’t know. But the timing is noteworthy.

Hamilton needed a new police chief. Two rival Inspectors vied for the vacant chiefship: Detective Inspector Joseph Crocker and Uniformed Division Inspector Tom Brown. Crocker was the favoured candidate.

Two days later, on Tuesday, 29 Nov 1938, another bomb exploded in Rocco Perri’s car. Again, he narrowly escaped with his life. Who planted the bomb? Was it the Buffalo-based Magaddino family?

Three weeks later, on December 21, 1938, the three-person Police Commission, including Mayor William Morrison (a close friend of Tom Brown’s and a former attorney for Rocco Perri), chose Brown, the old-school Inspector of the Uniformed Division, to succeed as the new Chief over his detective rival, Joseph Crocker.

If you were a major crime boss, and the current Police Chief wouldn’t play ball with you, what would you do? And which Inspector would you rather have as the new Chief? How far might you go to see your preferred candidate occupying the top job? More shadows.

The Mob Internment

On June 10, 1940, mere hours after Mussolini announced Italy’s entry into the war, Rocco Perri and his senior lieutenant, Antonio Papalia, were among the seventy-four Italians who were arrested and sent to the internment camp in Petawawa, Ontario. The RCMP and Hamilton Police took advantage of the War Measures Act to deal with the untouchable Rocco Perri and his lieutenants whom they’d been unable to convict for decades. Now they could be apprehended and interned without cause, simply because they were Italian.

Rocco Perri remained in internment for three years. Whereas, his lieutenant, Antonio Papalia, was released after only six months. Why was Papalia released so early? We don’t know. There is no recorded reason. More shadows.

Italian Canadians as Enemy Aliens

Papalia returned to Hamilton to find a power vacuum in the crime world. With support from the Magaddino family in Buffalo. Papalia quickly consolidated his power and took over as the new ruling crime boss in Hamilton where he reigned for the remainder of his life. Papalia had two-and-a-half years unopposed by Rocco Perri who remained in the internment camp. Papalia was so successful at shutting out Perri that he was even later able to pass on the leadership to his son, Johnny “Pops” Papalia, creating a two-generation dynasty that lasted until 1997.

On 17 Oct 1943, after three years behind barbed wire, Rocco Perri was finally released from internment. Aware of Papalia’s reign in Hamilton, Rocco withdrew to Toronto to plan his attempted return to power.

The Whisky King Vanishes

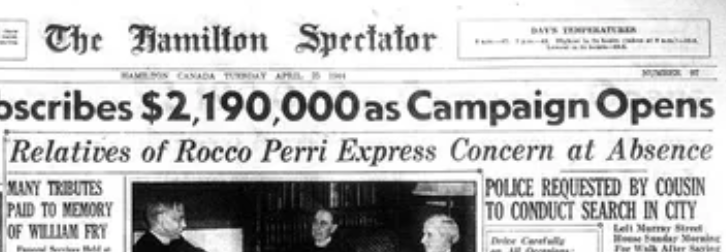

On Thursday, April 20, 1944, six months after his release, Rocco returned to Hamilton and began meeting with key friends and allies as he sought to regain control of the city. Three days later, on Sunday, April 23, 1944, while staying at his cousin’s house on the Hamilton Mountain, Rocco went for a walk and never came back. Two days later, on Tuesday, April 25, 1944, Rocco’s cousin reported Rocco’s disappearance to Hamilton police who conducted a brief, superficial and cursory investigation. Two days later, on Thursday, April 27, 1944, Hamilton Police released an inconclusive report on the disappearance of Rocco Perri and on that same day, Police Chief Tom Brown celebrated his 65th birthday and retired.

Rocco Perri’s body was never found. The Papalia family were implicated, but the case was never solved.

Happy birthday, Chief! Your key nemesis disappeared without a trace! Most of the records of the investigation also subsequently disappeared without a trace.

Lots of shadows.

Coincidence?

Tom Brown did not have the clout to arrange for Antonio Papalia to receive preferential early release, and he most certainly would have had no part in the demise of his predecessor, Chief Goodman. But was he involved in conversations with those who did have that clout to release Papalia? Was he a pawn in a larger game to dethrone Rocco Perri and install Antonio Papalia as a Magaddino puppet king successor in Hamilton? Or is all of this just a series of incredible coincidences?

I asked that question of James Dubro, esteemed Canadian crime journalist, CBC crime documentary producer, and co-author of the definitive biography, King of the Mob: Rocco Perri and the Women Who Ran His Rackets. His answer was an unequivocal “No, I don’t think that’s a coincidence.”

I asked the same question of Trevor Cole, author of The Whisky King: The remarkable true story of Canada’s most infamous bootlegger and the undercover Mountie on his trail. It did not seem coincidental to him either. His response was, “I wish I’d known more about your great-grandfather before I’d finished writing my book. I would have included an entire chapter about him.”

James Dubro is co-author of King of the Mob, Rocco Perri and the Women Who Ran His Rackets, and several other books on Canadian organized crime. He produced the CBC documentary series, Connections, on the history of organized crime in Canada. And he wrote the Canadian Encyclopedia article on organized crime in Canada.

I found myself struggling to write this piece without bias, to be clear in distinguishing between what I suspect is true versus what I know is true. Much of the evidence has vanished, necessitating speculation. However, the very fact that the evidence is missing may itself indicate that there was something worth covering up. The evidence that remains is sometimes ambiguous, but the picture it paints is persuasive. As we journey deeper into this story, I’ll do my best to distinguish between fact and innuendo. But I’ll be honest, it’s not easy to do.

Epilogue: Full Circle

In 1997, mob boss, Johnny “Pops” Papalia, son of Rocco Perri’s successor, Antonio Papalia, was murdered by brothers Angelo and Pat Musitano. The Musitano brothers were careless and were caught and convicted. After serving only nine years in prison, the brothers were released in 2006.

Papalia’s friends seem to have had a long memory and were patient enough to bide their time for the right moment.

In 2017, Angelo Musitano was murdered in his driveway in my suburban neighbourhood, only one kilometre from my home.

Three years later, in 2020, the same year that I first learned of my great-grandfather’s connections to the mob, Pat Musitano was murdered just blocks from where I used to work.

This story had come full circle from my ancestor to my doorstep.

Over the following chapters I will dig deeper into each of the events outlined here as I explore the intertwined lives of the Chief and the King.

Mobster Angelo Musitano shot dead in Waterdown driveway

0 Comments